Approach primer

Simplified Semantic Data Modeling (S2DM) - Approach Primer

Table of Contents

Background

Why do we need such an approach?

Subject Matter Experts are often NOT data modeling experts

Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) are often not familiar with data modeling, nor are they following best practices to formalize their knowledge. This lack in expertise can be problematic when they are in charge of expanding and maintaining a certain controlled vocabulary that will be used in real systems at the enterprise level.

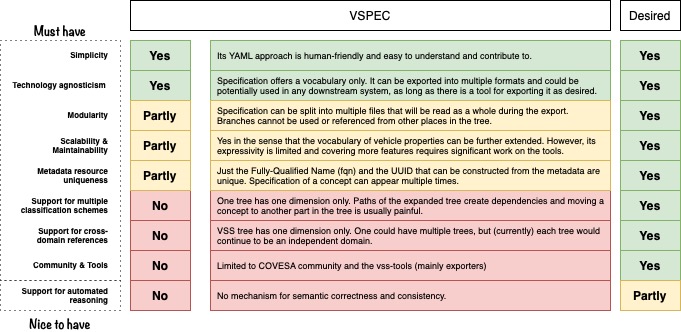

Vehicle Signal Specification has been an alternative but requires improvements

When it comes to vehicle data, the Vehicle Signal Specification (VSS) has been offering an easy-to-follow approach to enable SMEs contribute to a controlled vocabulary of high-level vehicle properties (e.g., Speed, Acceleration, etc.).

Vehicle Signal Specification (VSS) is a controlled vocabulary for the properties of a car organized in a hierarchical tree. To learn more about VSS, please visit the official documentation page.

The VSS modeling approach has been well received by SMEs who have been extending the list of properties both publicly at the COVESA alliance and internally at BMW.

However, this approach has reached its limits on what one can express with it.

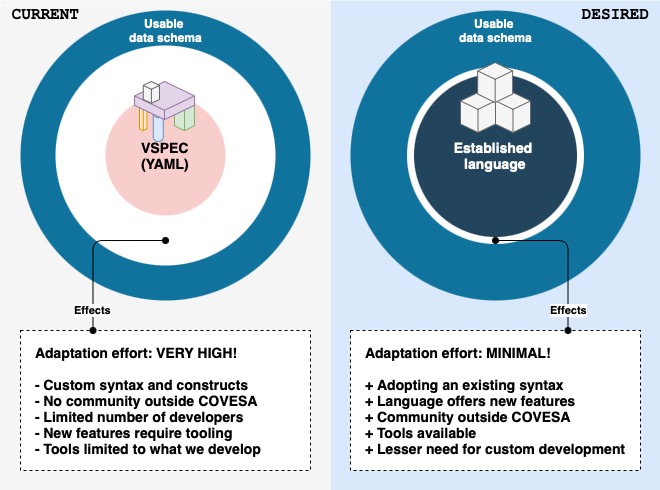

Among the limitations, is the fact that VSS uses a custom file extension .vspec that referes to files written in YAML with a custom syntax.

The language used in vspec, as of December 2024, does not support cross references.

Thus, it is not possible to model multiple inter-connected domains.

If you want to learn more about the current limitations of

VSS, please visit these resources:

The reference mapping between the Vehicle Signal Specification (VSS) and this S2DM approach is documeted in /docs/s2dm_vss_mapping.md.

Design principles

Problem

- Disparate vehicle data models that lack proper semantics.

Requirements

| Criteria | Requirement |

|---|---|

| Simplicity | Modeling approach is easy to follow. Its representation is not verbose. It is friendly for anyone new to the area. It is easy to add new concepts. |

| Technology agnosticism | Data model can be used with any downstream technology (e.g., by exporting it into multiple schemas). |

| Modularity | Data model can be split into multiple (reusable) small pieces. |

| Scalability & Maintainability | Model can scale up (e.g., concepts are extended). It can be easily maintained (e.g., changes and extensions are possible). |

| Metadata resource uniqueness | Concepts in the data model are uniquely identifiable with future-proof ids (e.g., by the use of International Resource Identifiers (IRIs)). |

| Support for multiple classification schemes | Polyhierarchies are supported to classify the terms in the vocabulary with different classification criteria (i.e., useful for data catalogs). |

| Support for cross-domain references | Multiple cross-referenced domains are supported natively by the language (useful for contextual data). |

| Community & Tools | Data model can be used in multiple up-to-date public tools. Modeling approach is based on a language that is already established in the open community. |

Goal

- To minimize the effort needed to develop, extend, and maintain vehicle-related semantic data models.

Artifact

- A guideline on how to model vehicle-related data with proper semantics and good practices.

Proposed solution approach

General workflow

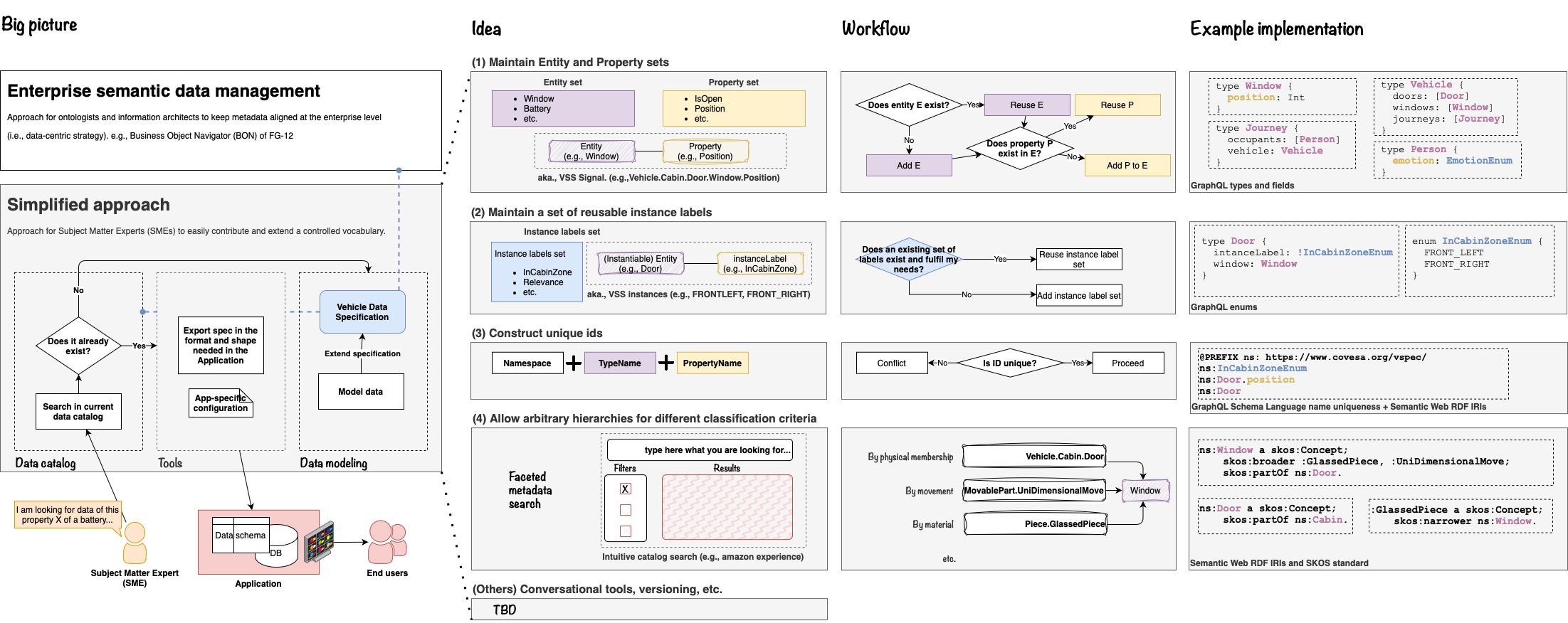

A simplified approach (see figure’s left side) could be the adequate bridge between the ideal enterprise metadata management and the actual use of a domain data model in an application. Specially in cases where SMEs are actively extending a set of data structures that are needed in practice. Also, when alliances or consortiums consist of multiple external stakeholders.

Overall, a SME should be able to intuitively search and find the data of interest via a data catalog. If the desired data is found, tools must allow the export of it into the structure needed in the application. In the case that no existing data matches his needs, simple steps must allow the modeling of the missing concepts. To that end, such a process is proposed with the following ideas:

Idea (1): Maintain Entity and Property sets

In an application, most of the value is centered around what one can read or write.

Thus, the most granular structure corresponds always to a certain Property (aka., characteristic, attribute, etc.). For example: the position of the window, the speed of a vehicle, the angle of the steering wheel.

All of them are assotiated to a particular datatype, such as Integer, String, etc.

Then actual values of those properties can have dynamic (i.e., data streams) or static behavior.

Properties belong to some Entity that is of interest for our application. For example:

Window, Vehicle, SteeringWheel, etc.

So, an Entity can contain a collection of properties.

The principal idea here is to maintain a set of entities and their assotiated properties.

Idea (2): Maintain a set of reusabel labels

In some cases, there are entities that can have multiple instances.

For example, A vehicle might not have one but multiple doors, windows, seats, batteries, tires, etc.

Hence, it becomes useful to avoid repetition in the modeling by allowing the specification of reusable labels.

A list of labels, such as InCabinZone, could contain the options FRONT_LEFT, and FRONT_RIGHT.

These could be used directly to specify a particular Door, Windows, and Seat.

Idea (3): Construct unique IDs

To foster reusability and avoid naming conflicts, a rule set must be enforced. The minimum constraints must be:

- A

namespace(ns) must be unique and future-proof. - Within a

namespace(ns), the name of anEntitymust be unique. - Within a

namespace(ns), the name of anEnummust be unique. - Within an

Entity, the name of aPropertymust be unique.

In the case of GraphQL schema language these constraints are supported.

One can concatenate the elements to create International Resource Identifiers (IRIs)

PREFIX ns: <mynamespacehere>

ns:Door

ns:Door.position

ns:Door.isOpenThen, IRIs can be used when defining the schema in the application.

For example, a json schema could look like:

{

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"door": {

"implementedConcept": "ns:Door",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"position": {"type": "int"},

"isOpen": {"type": "boolean"}

},

}

},

}Idea (4): Allow arbitrary hierarchies for different classification criteria

As the Entity and Property sets grow over time, proper information classification becomes essential.

The most tangible value of this organization is visible in any online shop.

There, a faceted search is the default tool for filtering the available data with specific criteria.

The same principle can be applied here.

For example, the Window entity can be classified by its physical position (Vehicle.Cabin.Door.Window), its principle of movement (MovablePart.UniDimensionalMove.Window), its material (Piece.GlassedPiece.Window), and by other criteria.

The Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) is a well-established standard to achieve such classifications.

Idea (5): Specify possible interactions

The entity and property sets (of idea (1)) can be complemented with an specification of the set of possible operations on them (i.e., interactions or actions). For example:

| Domain | Operation |

|---|---|

Seat |

Get the position of all seats. |

Seat |

Save a seat position to memory. |

Seat |

Control the heating mode of a seat. |

Climate |

Turn on/off the AC. |

Climate |

Set the temperature. |

Climate |

Get the fan speed per zone. |

Other ideas:

TODO: Conversational tools, versioning, etc.

Examples

Refer to the examples folder.

Special considerations

The following cases require special treatments.

Dilemma: Property as field or as object type

Here’s the markdown summarizing the three cases for your dilemma:

Case 1: Scalar Field

type Vehicle {

speed: Int

}Pros:

- Simple and concise representation.

- Easy to read and understand for straightforward use cases.

- Suitable for static properties that do not require additional metadata or complexity.

Cons:

- Limited extensibility: Adding metadata (e.g., units like “km/h”) or additional attributes (e.g., timestamp) requires refactoring.

- Not future-proof: If the property evolves to include more details, significant schema changes are needed.

- Cannot represent complex relationships or metadata.

Case 2: Dedicated Object Type

type Vehicle {

speed: VehicleSpeed

}

type VehicleSpeed {

value: Int

unit: String

timestamp: String

}Pros:

- Highly extensible: Allows adding metadata like

unitortimestampwithout breaking the schema. - Better suited for complex properties: Can easily accommodate additional fields like ranges or error margins.

- Future-proof: Supports evolving requirements without major schema changes.

Cons:

- More verbose: Introduces additional layers of nesting, making the schema longer and more complex.

- Overhead for simple properties: Feels excessive for straightforward fields like

speed. - Harder to read and maintain for basic use cases.

Case 3: Reusable Property Type

type Vehicle {

speed: IntProperty

}

type IntProperty {

value: Int

unit: String

timestamp: String

}Pros:

- Reusability: The

IntPropertytype can be used across multiple fields (e.g.,speed,weight, etc.), ensuring consistency and reducing duplication. - Extensible: Like Case 2, it supports adding metadata or attributes without schema refactoring.

- Consistent: Standardizes the representation of similar properties across the schema.

- Future-proof: Accommodates evolving requirements while maintaining schema clarity.

Cons:

- Overhead for simple properties: Adds complexity for fields that don’t require metadata.

- Generic naming: May feel less descriptive compared to dedicated types like

VehicleSpeed. - Potential for overgeneralization: If properties diverge significantly, the reusable type may become too generic.

Recommendation

- Use Case 1 for simple, static properties that are unlikely to evolve or require metadata.

- Use Case 2 for properties that are unique and require specific metadata or complex structures.

- Use Case 3 for properties that share common metadata or structures across the schema, ensuring reusability and consistency.

For vehicle-related information, Case 3 with a reusable type like IntProperty is often the best choice, as it balances extensibility, reusability, and clarity.

Enums’ datatypes

In GraphQL, enums are typically used to define a set of allowed values for a field. These values are usually represented as strings, such as [FIRST, SECOND, ...]. However, GraphQL enums are not limited to strings conceptually; they can represent any discrete set of values.

If your model defines “allowed” values as integers, like [0, 1, 2, ...], you can still use GraphQL enums to represent them. Internally, GraphQL will treat these enum values as strings in the schema, but you can map them to integers in your application logic.

enum TheAllowedValues {

ZERO

ONE

TWO

}In your application, you can map ZERO to 0, ONE to 1, and so on. This approach allows you to enforce a fixed set of values while maintaining flexibility in how they are interpreted in your code.

Special cross references

GraphQL schema language excels in defining the structure of data models in a clear and understandable way. It provides robust elements such as types, fields within types, nested objects, and enumerations. These features allow for a well-organized and precise representation of data structures. However, it has limitations such as restricted cross-references, where linking fields to other fields directly is not possible.

Let us assume our model has the concepts Window.position, AC.temperature, AC.isOn, Sunroof.position.

In the GraphQL schema language, it is not possible to say that the Person.perceivedTemperature can be modified by acting on these properties.

type Window {

position: Int

}

type AC {

temperature: Float

isOn: Boolean

}

type Sunroof {

position: Int

}

type Person {

perceivedTemperature: Int # I want to say that this property might be affected by acting on the others

pTemp: PTem

}

type PTemp{

affectedByProp: Property

value: String!

}

type Property {

objectName: String!

fieldName: String!

}Option 1 - Instance data file

An alternative would be to define the schema as usual, and then write another instance data file with concrete instance data that represents the connections. For example, that the perceived temperature is affected by Window.position, AC.temperature, AC.isOn, Sunroof.position.

Option 2 - Enums with URIs

However, the following is possible and supported by the language out of the box by using nested objects:

type Person {

perceivedTemperature: PerceivedTemperature

}

type PerceivedTemperature {

temperature: Int

modifiableBy: [perceivedTemperatureModifiersEnum]

}

enum perceivedTemperatureModifiersEnum {

ns:Window.position

ns:AC.temperature

ns:AC.isOn

ns:Sunroof.position

}Option 3 - using directives

```graphql

directive @affectedBy(object: String!, field: String!) on FIELD_DEFINITION

type Person {

perceivedTemperature: Int

@affectedBy(object: "Window", field: "position")

}

type Window {

position: Int

}